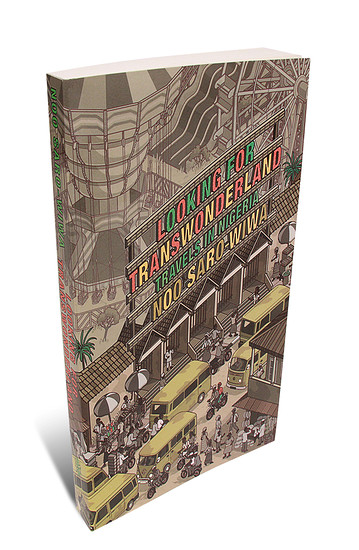

Book Title: Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria

Author: Noo Saro-Wiwa

Publishers: Soft Skull Publications

Year of Publication: 2012

Reviewed by: Nana M’bawa

In Looking for Transwonderland, Noo Saro-Wiwa writes about the experience of going back to her home country, Nigeria, after having been away from the country since 1990, with brief visits in 2000 and 2005.

There is a contrast between this visit and others she had made in the past; as a child, she had been forced to visit Nigeria by her parents. Saro-Wiwa grew up in the United Kingdom, and having to go back to Nigeria on a regular basis was not something that she looked forward to. It was, however, a part of her childhood, and of growing up.

In 1995, Nigeria became associated with a brutality that directly affected the writer; her father, writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, was hanged during the Abacha regime. As Saro-Wiwa points out in her book,

My father’s murder severed my personal links with Nigeria. Though safe to travel, I was not obliged by mother to go there any more, nor did I have the desire. Nigeria was an unpiloted juggernaut of pain, and it became the repository for all my fears and pains… (18)

And yet, about a decade later, she made a decision to go and visit Nigeria. For one thing, she was, at this time, a travel writer, and had already written about other countries in West Africa. She thus felt the need to explore and write about her home country (19). She was also inspired by the fact that her brother, Ken Jr, had gone back to Nigeria and settled ‘without losing his sanity’(19).

As creative non-fiction situated in the travel-writing genre, Saro-Wiwa’s book rightly pays detailed attention to the different spaces that are described. But what I found particularly interesting was the contrast between physical and mental spaces. Take, for instance, the beginning of the journey to Nigeria, when the writer is at Gatwick Airport. The flight to Nigeria has been delayed, and the passengers are annoyed. Saro-Wiwa describes the reactions of her fellow-passengers, how they ‘huffed and pontificated’ as well as the rather blasé reaction of the airport officials. But the airport scene also kick-starts a memory in 1983; that of a similar airport scene, and of memories of childhood.

Sometimes memory comes in the form of places she did not get to visit. For example, when she goes to Ibadan, one of her memories is that she was not able to visit the place when she was with her father in 1988. Visiting it many years later brings memories of her father, especially since he had studied at Ibadan.

I would describe Looking for Transwonderland as a journey within journeys; journeys of pain as the past is relived, journeys filled with laughter as the author pretends to be a woman in her fifties in order to find out more about Nigerian gigolos. There are fast-paced journeys as the author hires motorbikes to travel from one part of the different cities to another, and the more reflective, introspective journeys as she thinks about childhood.

Reading the book, I was struck by the references to the masked dancers. There is an incident in the book during which the writer meets a masked dancer, and as I read it, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘Hmm. This is something that could easily happen in Malawi too.’ This was Noo Saro-Wiwa’s journey, but virtually partaking in it meant, in some instances, recalling related experiences for the reader.

I could not help thinking that writing this book required a balancing act, and in my mind I imagined several characters; Noo the writer, giving the reader powerful descriptions drawn from memory, research, and observation, but also Noo the traveller, going back home, exploring, reliving her past, Noo the adult, remembering childhood.

It is a balancing act in which not a single ball was dropped.

*************

Note to our readers: We would love to know what you are reading, or if there is any film or music album that has caught your attention. Feel free to send us book, film or music reviews.