By Tikondwe Chimkowola

My baby only knew two colors: White and Green. The white from our uniforms and the green of the prison warders. He always cried when someone else in a different colour came around the cells. I chuckle at this thought as I wipe his forehead. It is past midnight and I cannot sleep, I sit up and watch the tiny beads of sweat that gather and streak down his forehead. His fever is getting worse, I can see it from how he continuously cries in his sleep. He clutches the little stuffed doll I made him in my needle work class when he was about three months old, I believe a good mother is supposed to make toys for her children. I rub the sweat off his forehead with the hem of my uniform before I lay down to catch some sleep. But, I still cannot not sleep, I am impatient with how slow time is moving, I am to go to the hospital with the baby this morning. “Only a few hours left till morning” I whisper to myself, but there is a heavy feeling on my chest that makes me feel like I am choking on my own breath.

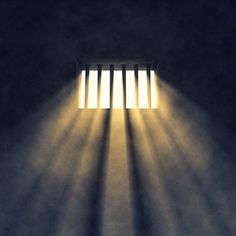

I was incarcerated on 3rd April 2013 on charges of drug trafficking. My boyfriend, on the other hand, was granted bail and that was the last we saw of each other. I was confused, angry and afraid but I had to come to terms with my new life. I was teased, stripped naked and humiliated by my fellow women in prison on my arrival. I couldn’t eat or sleep, sometimes during the night I would wake up screaming, tearing at my hair. They all thought I was mad, so they put me in isolation. I began noticing that I would wake up feeling nauseous, I had not bled ever since I arrived but I thought it was because of bad food. One day the nyapala called me under the tree, she devilishly smiled then whispered “I know you are pregnant… now tell me which one of these bastards did this to you”. You see during the night the warders would come into each cell to pick out women they wanted to sleep with, some went willingly because of the favors they would get from the warders: to get a bigger portion of the nsima and fish stew, that had more bones than fish to it. Others would be brutally raped but the female warders told us to be silent about it. When Maria, the youngest in our cell, a girl of twenty-two was raped by one of the men in green, she came back with blood stains on her white uniform. She sobbed throughout the night and the other women did nothing but to watch her with pity and remain silent. You see…in here, what happens here stays within the walls, of course when you rest your head on a wall you can hear the muffled screams, the whispers of empty promises of freedom and privilege coming from a drunk warden’s lips. But beyond the walls, there is nothing but silence.

I went to the hospital after our little conversation and doctor confirmed my biggest fear. My ears went deaf. It was one of those situations where your body goes numb and cold, you are not sure if you are dreaming or hallucinating. You wonder why you still haven’t woken up from such a painful dream, the pain continues to coil within your heart until you realize that this is actually happening and it’s not a dream. I was brought back to reality when the nurse signaled me to follow her to the pharmacy. My blood levels were low and I was malnourished. The nurse asked me if I still wanted to keep the baby, I was still confused and I mumbled a few incoherent words I still cannot remember. She handed me some small pills in a pink paper and assured me that they will take care of the needful.

When I showed them to my friends, they all assured me that they were abortion pills and that I had to take them. “Why should you struggle to bring a child into this wretched place, only for it to suffer” said the fat lady that always sat in the corner. “No, she can always send her baby home, she must still have relatives somewhere” said Nyanyiwe, the older woman who always covered herself with a thin tattered chiperoni blanket. Rumor had it that she had two babies during her eighteen years in prison, but both were taken to an orphanage.

The fat lady in the corner stood up angrily. “But how many times have those children visited you Nyanyiwe! Which child would be proud to know that its mother is behind bars?” she then looked at me and said, “ The moment that child leaves that gate, you cease to be its mother, in fact , forget that you’ve had a baby… why are you even wasting time? Get rid of it already”. I was in a fix, so I kept my pills in my small green pencil bag and hid it under my mat.

When I had made up my mind, the pills had vanished. I learnt that they were gold in this place. Someone must have stolen them. I was furious. I stormed out and went to the maize field to cry. Little did I know that I was in no woman’s land, two male inmates found me there and what happened next is what nightmares and horror movies are made of and you probably do not want to hear it, and even if I said it, you wouldn’t really do anything about it. I woke up in Nyanyiwe’s face, I was in the cell, the women were telling me how they had found me, everyone was asking me what had happened. I was weak, my head was pounding and their noise was irritating, everything became blurred and I think I may have lost consciousness again. Everyone advised me to remain silent about it, they told me I would only get myself into more trouble if I told anyone about it.

I felt no use for living. I now loathed the man who had made me pregnant, a man who I had thought loved me, who I adored because we lived life in the fast lane together, now he had left me to crash, and he’d obviously found a replacement. Adding salt to this wound was the fact that I had been raped by two men and told to say nothing about it. I felt like I was in a prison within another prison… the walls of the prison confined my freedom, but my woman’s body felt like another prison. “This baby must go,” I whispered to myself. I went and asked the nyapala who advised on how a simple solution of water and washing powder does the trick. So with the little money I gathered I bribed one of the female warders to bring me a packet of Sunlight. I took guts for me to chuck down the solution and moments later my lower abdomen was on fire. They told me to rest and wait for everything to fall into place. But there was nothing, no blood just a burning pain. I could not sleep that night and I was eventually taken to the hospital.

After I returned from the hospital, the fat lady who always sat by the corner came to me and asked me to follow her to the banana field. Along the way, she told me she had a way of helping me abort the pregnancy. She praised her method, telling me that she had helped so many women get rid of the fruits of molestation they carried in their bodies. Between the banana stems, was a well-crafted bed made from banana leaves and stems, but what chilled my body were the materials being prepared for the operation: a rusty hanger and a few seemingly sharp instruments. A gush of fear and nausea surged through me, I felt my legs weaken and my knees began to shake. I was convinced that my heart would not let me go through this. I finally understood why the pills were stolen, people had to shake hands with death and hope they still live to fight another day. Before anything else was said, I found myself walking towards what I thought had now become home.

I gave birth prematurely, on the very same banana leaf bed on a chilly November night with the help of Nyanyiwe and a few other women. One of the twins was still born, so the women quickly disposed it off before I could see it. The tiny baby boy was bathed and wrapped in Nyanyiwe’s blanket and handed to me, so I could see his face and give him a name. They all sang and jubilated at the birth of the baby, it reminded me of home, how my mother and my aunts would have danced and ululated at the birth of their grandson. But this was a grandson they did not know about. Even if they did would they accept the child of a social outcast? A frail premature baby whose life was uncertain. The next morning I saw him in the hospital nursery, I felt hope, I wanted him to grow, I wanted him to be happy. I pictured him playing around with the other children in the walls. The children gave us hope and inspiration, the prison walls may have confined them to one space, but their minds soared everywhere especially when they would start going to the tiny pre-school by the prison. But sadly, only a few made it that far, the diet was bad and the cells were a mine for diseases and they would die before age three.

Motherhood was not easy for me, since we only got a small ration nursing the baby was difficult, the other women of the cell had to share their rations with me so that I could still be able to nurse. As time passed, these women became mothers, aunts and sisters to me. Our needle work classes were filled with laughter although there was so much sadness hovering above us. Nyanyiwe taught me how to make stuffed dolls, which I made for the baby. He always giggled as he tossed it around, seeing him happy made me happy in a way, I must say I was a proud mother in what some would call the wrong place. However, my happiness seems to have been short-lived as at only nine months, just when he could crawl his own, he fell ill, an endless fever had gripped him. He would vomit anything that went in his mouth, including his own mother’s milk.

I wake up sweating. Through the tiny window I see the light of dawn between the bars, my thoughts drift to the baby, I have to get him ready for the hospital trip. When I touch him, he is cold, he has a gaze that seems to be fixed on me but he does not move. That is when I realize that he is dead, he probably died while I had dozed off. I feel a pain in coil in my womb. I scream. Life has betrayed me. The women wake up and tell me we have to arrange a secret burial. They dig a shallow grave and I lay him in there. He still has that ever peaceful look, one would think he had just fallen asleep. We bury his body without a coffin, just his stuffed doll.

For the rest of the days until I am pardoned I become the lady in the corner. I sit there talking to myself. On the day I leave the prison, the women give me a multitude of letters, they ask me to deliver them to their loved ones, and I carefully pack them in the green pencil bag. It is interesting to see how these women still have so much love for the world out there, but the question is, does the outside well still love and ache for letters like these? These are questions I want to find answers for, and as I leave, I ask myself whether this story is worth telling when the only person who knows my strength and my love is dead. I sigh and simply tell myself not to be too hopeful that people will listen to my story, for what happens in prison stays within the barb-wired walls.